European migration management policies operate under several flawed assumptions. The first such assumption is that in the absence of cooperation with Libya, controlling hubs of irregular migration such as Agadez will stem the flow of those destined for Europe. It is important to consider that the large majority of migrants see Libya and Algeria as their final destination. However some contend that the hardening regional migratory controls and deteriorating situation in Libya have pushed them further towards Europe.

This can partially be explained by the second flawed assumption in migration policy, which assumes that further securitization will deter irregular migration. In short stricter controls push smuggling and trafficking further underground and as a result push migrants towards more costly and dangerous routes.

European initiatives in the Sahel are not solely devoted to securitization however. Instead they encompass a blend of security and development objectives. The flawed assumption present in this approach is that development does not lead to reduced migration. In reality development is shown to increase migration in the short to medium terms. Regarding outward migration from poor countries to wealthy nations as something that needs to be stopped is somewhat biased as developed nations’ labour forces tend to be highly mobile.

It is important to consider not only the assumptions underlying both the securitization and the developmentalization of the efforts to deter irregular migration, but also how they have become linked. More specifically, development assistance has become directly tied to the security interests of donor nations. In the Sahel, development assistance from the European Union comes with the stipulation that receiving countries must make tangible efforts to curb irregular migration across their borders. This influences migratory control in two important ways.

First, security actors now exercise expanded roles, which includes providing humanitarian and development assistance as well as providing basic civilian law enforcement. Controlling migration has transitioned from coercive tactics towards symbolic (ie judicial) control.

Second, security institutions now have a greater influence in the distribution of development assistance. This means that development assistance funding can be diverted to security actors as their activities now fall under the development mandate. Critics argue that funding has been diverted from poverty alleviation and meaningful capacity building initiatives towards well established elites within the security community.

The situation becomes even more complex when considering that Europe is simultaneously pursuing two divergent security imperatives in the Sahel : 1) combating violent extremism in the region, and 2) cracking down on irregular migration. Niger is an outlier in terms of stability in West Africa, and is therefore a valuable European ally in the fight against violent extremism, while simultaneously being a major transit country for refugees and migrants alike.

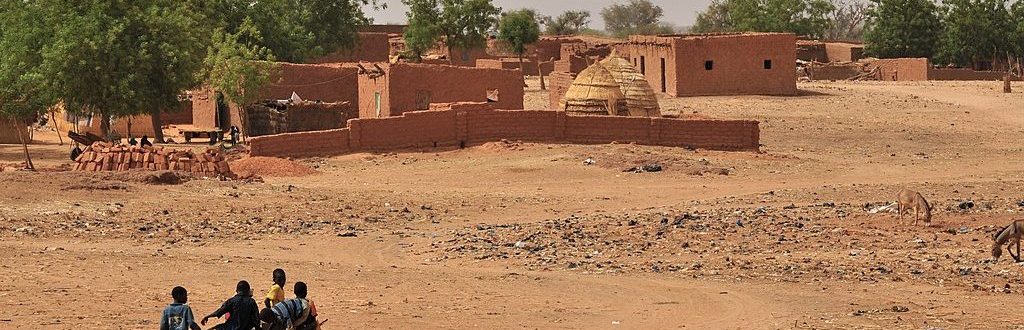

In the case of Niger, the increased insecurity resulting from Qadhafi`s fall in 2011, the Malian rebellion in 2012, and jihadist attacks on both the northern (Algeria and Mali) and southern border (Nigeria) have meant that stability and security are Niger’s number one priority. Maintaining stability within Niger has historically meant appeasing northern tribal elites. These elites are often directly tied to illicit cross border trade, while those who are not would not risk political suicide by intervening. These groups effectively rule the north of the country and are connected to similar groups in Northern Mali and Libya as a result of illicit trade relations and tribal ties.

Because trans-Saharan smuggling networks play a vital economic role for many communities in one of the world’s poorest countries, cracking down on irregular migration has a destabilizing effect. In the face of increased security, migrants are more likely to pursue more dangerous routes and avoid interacting with local communities all together.

Return of the Generals? Global Militarism in Africa from the Cold War to the present.

Rita Abrahamsen

2018

This paper outlines the transition of Cold War militarism to its contemporary counterpart : global militarism. It argues that narratives surrounding development and security have made the modern rendition of militarism paradoxically more prone to war. African militarism during the Cold War was focused on stability, with the military playing an active role in the maintenance of order.

Contemporary militarism has become linked with poverty reduction and capacity building. Framing underdevelopment and poverty as security issues has enabled traditional security actors to become involved in receiving and distributing development assistance. It has also enabled development funding to be allocated to security activities. Donor states now link development assistance to their security interests, which incentivizes recipient states to encourage narratives of violence associated with poverty, but also to present domestic insurgent groups as threats to international stability.

The risks associated with this shift include the potential for funds for poverty alleviation to be instead allocated to members of the security sector, increased political influence of military actors in recipient countries, more efficient suppression of political dissent in the name of security, and the erosion of democracy.

Development and Migration – Migration and Development: What Comes First?

Stephen Castles

2009

The author challenges the two primary assumptions of prominent policymakers regarding migration from less developed countries. The first is that migration of poor people to wealthy areas is inherently bad. Second, that development (reduction in violence and poverty) will stem migratory flows. He contends that evidence suggests that reductions in poverty and violence actually increase migration. These assumptions guide policy measures, such as tying development aid to unwanted migrant returns, or reinforcing border controls in transit countries. This paper goes on to suggest that migration is conceptualized on the basis of political need.

African Migration to Europe: Obscured Responsibilities and Common Misconceptions

Dirk Konhert

2007

This paper argues that deterrence policies push migrants to irregular routes, encourage smuggling and expose migrants to unnecessary dangers. The perceived “root” cause of migration (underdevelopment) can partly be attributed to the European Union’s trade policy which undercuts the development of essential industries within Africa. Lastly, the EUs response to curb irregular migration through the promotion of economic development is flawed, as development is shown to increase migration in the short to medium terms.

Militarism and its Limits: Sociological Insights on Security Assemblages in the Sahel

Philip Frowd

2018

This article argues that viewing security efforts in the Sahel through the lens of militarization is insufficient in capturing the shifts occurring within intervention practices in the region. International efforts attempt to restrain the use of coercive force, or the appearance of supporting further militarization due to the associated political cost. Instead securitization efforts blend conventional military responsibilities with capacity building initiatives and civilian law enforcement. This article argues that the blurring of the lines between military and traditional civilian institutions represents a transition in managing irregular migration from conventional coercive tactics to the reinforcement of conventional forms of civilian control (i.e. symbolic state violence)