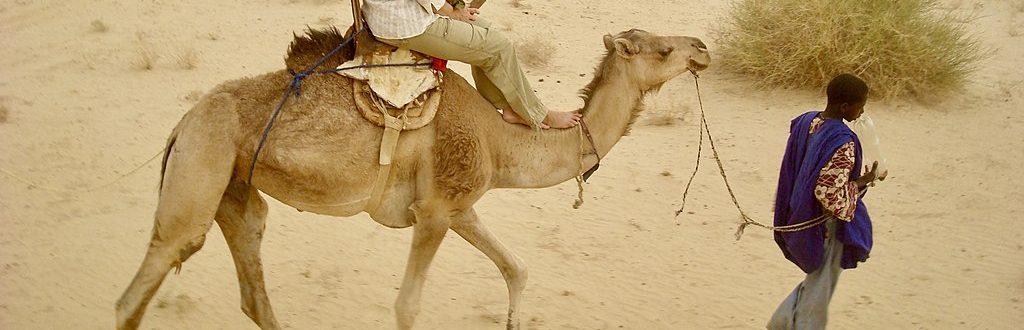

The current form of human smuggling within the Sahara can trace its roots to the history of trans -Saharan trade discussed in the previous point of entry. Truck drivers headed for Northern Africa would often taxi seasonal labourers and irregular migrants alike as means of obtaining supplemental income. This behaviour was frequent and was viewed as socially legitimate in the eyes of the local population as it ;

i) entails two parties voluntarily engaging in a transaction

ii) was commonplace in everyday life

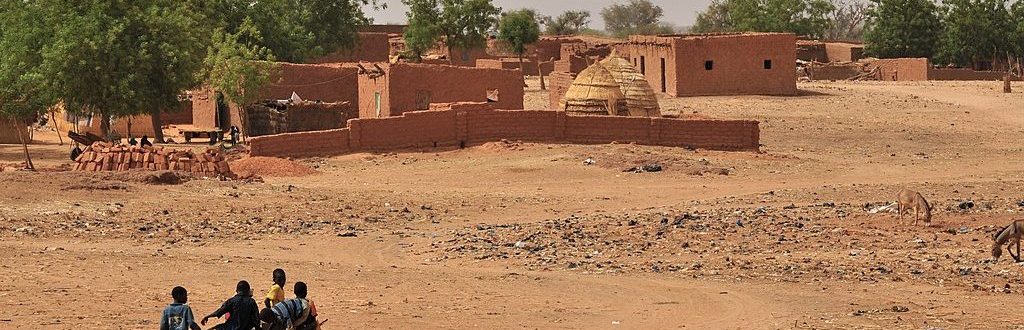

The industry further developed as a result of the Nigerien (The Republic of Niger) state’s appeasement efforts towards former rebel leaders in the north. More specifically the establishment of formalized travel agencies (often transporting irregular migrants across the Sahara) created employment opportunities for many former rebels. These rebels skills and knowledge required to navigate the Sahara that they developed during the conflict was integral to their new roles as drivers. The eventual breakdown of tourism in the region after 2011 led smuggling to become the lifeblood of many communities.

In 2015 under pressure from the European Union, Niger officially criminalized human smuggling. European interventions were premised on the fact that human smuggling within Niger is operated by transnational criminal cartels and jihadist groups. The opposite is in fact closer to the truth. Human smuggling (in Niger) is often a clandestine operation with minimal coordination (i.e. smugglers are often self-employed). This loose organization and cooperation on an ad hoc basis enabled smugglers within Niger to quickly adapt to and bypass stronger controls.

The aforementioned criminalization did little to stem irregular migration and led to the development of a state sponsored protection racket. More specifically, migrants were often able to bypass checkpoints completely by taking more dangerous routes or pass through them in exchange for bribes to security officials – a practice that became so normalized and embedded that some point out it has become essential to the funding of local police forces.

The EU eventually adopted a more aggressive stance, tying conditions to 1 billion of development aid. What resulted was a crackdown by Nigerien authorities against smugglers. However critics quickly point out that the crackdowns were often targeted towards ethnic minorities, those detained were convicted without due process and little was done to challenge the state sponsored protection racket. The failure of such policies can be explained by the entrenchment of human smuggling within the political economy of the region.

Understanding the significance of human smuggling in the local political economy requires understanding the multitude of actors involved and their relation to the (informal) industry.

These actors include transit companies who facilitate the movement of irregular migrants, local communities who rely on smuggling for their livelihood, security officials whose bribery and “taxation” of irregular migrants sustains local police forces, political elites who derive power from their ties to the industry, and armed groups who are strengthened through their exploitation of irregular migrants.

The next important dynamic to consider is the variability of smuggling operations across different stretches of the migratory route. The central governments of Libya, Mali, and Niger all exert minimal influence over the region, as such they do not provide the traditional forms of state security (border control, conventional security, rule of law). What is instead in place is a mosaic of formal and informal actors exerting influence over different localities. These include conventional security actors, Islamist groups, criminal organizations and local community memebers. These actors determine the localized dynamics of the three distinct stages of the trans-Saharan migratory route.

1) The legal route from West Africa to Northern Mali and Niger : characterized by formal transit companies working in tandem with the state protection racket.

2) The route within Northern Niger : characterized by human smugglers and state security forces.

3) Northern Mali and Libya : possesses many predatory armed groups in the absence of any state control.

Human smuggling networks are often composed of small independent links in a larger transnational chain. As such they are highly adaptable to stricter controls, often at the expense of migrants whose journeys become more costly and dangerous. The danger of trans-Saharan human smuggling networks is not their facilitation of irregular migration, rather the threat they pose to state institutions by empowering irregular armed forces and corrupting state security forces.

Manufacturing Smugglers: From Irregular to Clandestine Mobility in the Sahara.

Julien Brachet

2018

Brachet outlines the historical context surrounding migration routes through the Sahel. Namely, the economic and socio-political drivers that led to the formalization of human smuggling as an industry. The paper then moves on to discuss the impact of European crackdowns on migrants and smugglers alike. Critics argue that the security apparatus being used to crackdown on smugglers has been abused while simultaneously pushing migrants to more dangerous routes.

Human smuggling across Niger: State-sponsored protection rackets and contradictory security imperatives.

Luca Raineri

2018

This article outlines how human smuggling networks have become normalized in Niger. Normalization has occurred to the point that a protection racket (security officials allowing human smuggling to occur in return for bribes) has developed within Niger’s security institutions. It goes on to argue that European efforts fail, and will continue to do so, because of the role that human smuggling plays in stabilizing the precarious political situation and the economic benefits it provides to underdeveloped communities across the country. Ranieri goes on to discuss that Europe is simultaneously pursuing two divergent security aims (preventing human smuggling and combatting terrorism) in Niger. Because Niger is a valuable European ally in the effort against terror groups in Africa, clamping down on human smuggling would destabilize the country and in turn enable terror groups. Therefore European initiatives reinforce the current positions of power in Niger, which in turn reinforces the protection racket surrounding human smuggling.

For the Long Run : A Mapping of Migration Related Activities in the Wider Sahel Region

Jair Van der Lijn

2017

This paper outlines patterns of irregular migration within Western Africa. It also covers the various European-led operations targeting human smuggling in Niger, Mali, and Libya. It goes on to outline the entrenchment of migration within the political and economic contexts of the region. The author calls for the establishment of more legal forms of migration while also promoting a comprehensive strategy. Key points include emphasizing greater cooperation and coordination between international and local actors, expanding the focus beyond transit countries, and putting more emphasis on addressing push factors in origin countries.