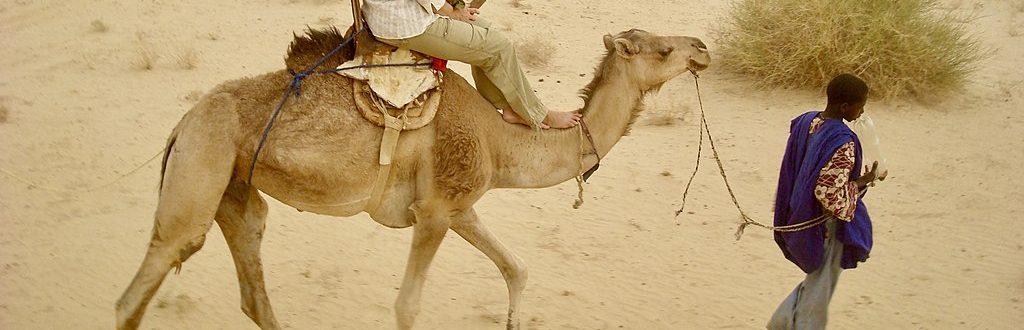

Trans-Saharan migratory routes frequented by refugees on their journey towards Europe have a long history. These routes are century old transnational trade networks which originated based on kinship and ethnic ties. The highly interdependent nature of the region’s economies, as well as the role migration plays as a coping mechanism for many has entrenched population movement as a staple of the region.

Pre-colonial migration revolved around trade and religious pilgrimages. Prominent contemporary examples of intra-African migration include former nomadic tribes migrating for work to the oilfields of northern Africa in the 1970s-80s and Libya’s policy of pan-Africanism between 1998 and 2007, which saw large amounts of Sub-Saharan labour enter into Libya’s agricultural, resource extraction and domestic industries.

Colonial rule in the early 19th century disrupted traditional routes while also creating new internal migrations as a result of rapid urbanization. The trans-Atlantic slave trade, which displaced roughly 12 million Africans, in tandem with the development of industries such as cocoa created new migratory poles across western Africa. Migration to Europe during the colonial era was concentrated in the French Maghreb. Migratory routes developed in response to France’s requirement for unskilled labour, routes which persisted even after Algeria’s independence in 1962.

Western European nations experiencing post war economic booms prompted the next wave of African-European migration. The oil crisis of 1973 redefined European attitudes towards African migration, shifting from the recruitment of labour to restrictive immigration policies. Since the late 1980s African migration to Europe has become concentrated towards the informal economies of Southern Europe and the modes of entry became more irregular as a result. The aftermath of colonial rule in Africa brought with it the creation of many independent states whose borders intersect various tribes, clans, and ethnic groups. This is important to consider as it convolutes contemporary understandings of concepts utilized to address irregular migration. For instance :

“Hence, while the borders did control some migration, they created new forms of migration by reshaping ‘political and economic opportunity structures’. This is seen most clearly in the case of refugees, who can only gain international recognition and protection if they leave their country of origin. The arbitrary nature of the borders means that distinction between international and internal migration is somewhat muddied in the African setting. In many cases, a move to a neighbouring country may involve less social and political upheaval for the migrant than a move to the capital.” From : “African Migrations: continuities, discontinuities and recent transformations” Oliver Bakewell and Hein de Haas (2007)

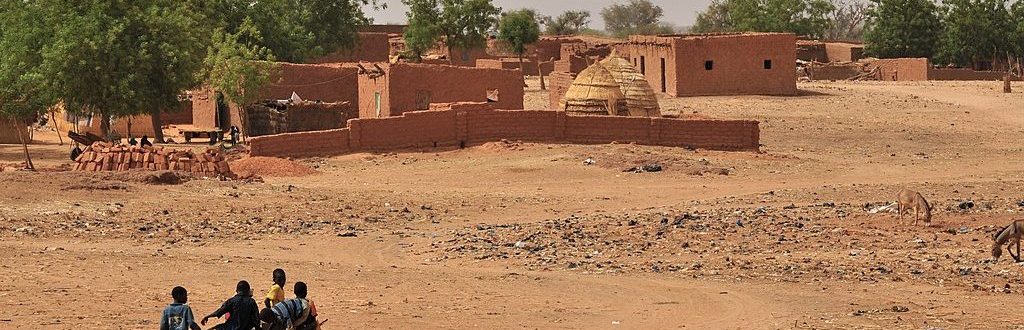

A large majority of the groups operating within the trans-Saharan route are often disenfranchised minorities of Libya, Mali and Niger. These groups’ livelihoods are often highly dependent on illicit trafficking and human smuggling, so much so that they have replaced the formal national economy as the main source of economic development.

African Migrations: continuities, discontinuities and recent transformations.

Oliver Bakewell and Hein de Haas

2007

Challenges the conventional focus of African towards Europe by highlighting the various inter-continental systems of migration. Bakewell and de Haas outline the shifting dynamics that influenced migration throughout different epochs in Africa. Most notably highlighted are the pre-colonial, colonial, and post colonial history of the region.

Europe’s Unknown War

Frances Webber

2017

Webber argues that the European nations use of readmission agreements overlooks blatant human rights abuses and violates fundamental principles of non-refoulement. There is a long history of circular migration within Western Africa. Only a small minority of migrants who cross the Sahara intend on reaching Europe. The author points out that hardening the anti-immigration climate in transit countries might increase the push towards Europe. They go on to argue that smuggling is deeply entrenched into the local political economy of transit countries, and targeting it without offering meaningful alternatives for economic or political development is counter-productive.

Turning the Tide: The Politics of Irregular Migration in the Sahel and Libya

Fransje Moleenar and Floor El Kamouni – Jansen

2017

This paper outlines the entrenchment of human smuggling within the political economies of Niger, Libya, and Mali. It outlines the multitude of actors and regional differences within the present along the trans-Saharan migration route. It provides an outline of current policy failures and offers recommendations on how to address irregular migration in the region.