Support the INDIEGOGO Campaign to buy solar powered lamps for refugee and local university students in Dadaab, Kenya , These lamps will enable them to complete schoolwork at home.

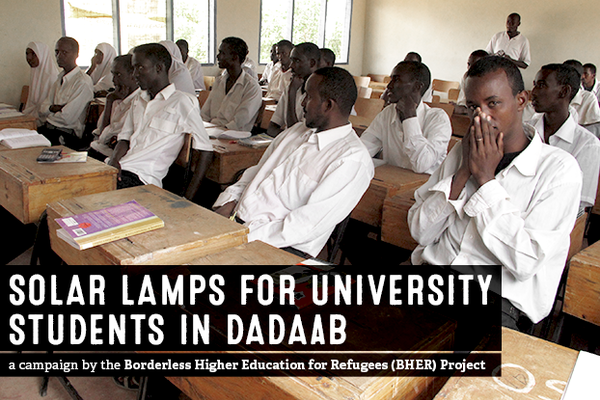

The Solar Lamps for University Students in Dadaab campaign aims to provide solar-powered desk lamps to refugee and local students in Dadaab, Kenya who attend tuition-free post-secondary education programs offered for the first time ever in Northeastern Kenya through the Borderless Higher Education for Refugees (BHER) project.

**Contributors who wish to receive a receipt for their tax-deductible donation should include their full name and mailing address when making their contribution.

The Borderless Higher Education for Refugees (BHER) Project provides educational programs in one of the largest refugee camps of the world, Dadaab, Kenya. The BHER project also creates space for local Kenyan students in Dadaab to benefit from these programs. Completion of these programs keeps women and men from precarious forms of employment and wins them internationally recognized credentials and marketable skills that they can use to work in situ, to be employed in Kenya, in their country of origin, or wherever they resettle.

A significant barrier identified by BHER students to completing their coursework is the inability to find adequate lighting during the evening. For many students, the ability to access study space with electricity and adequate lighting is often limited outside of class time. The restrictions for women students are often greater because of responsibilities that require them to be home in the evenings and also because of safety concerns faced by women when going out after dark.

A simple solution with a broad impact, solar-powered lamps give students the freedom to complete coursework at home and enable them to succeed in their university programs. However, the cost of lamps puts this much-needed resource out of reach for students, who already face livelihood challenges under the constraining conditions in the refugee camp and locally. While students in the refugee camps have access to meager “incentive” wages (approximately 102 CND/month for highly paid refugees), these earnings are barely enough to support themselves and their families. Students from local communities may be paid at a slightly better rate (around 200 CND/month), though this amount is still highly restrictive. For both refugee and local students, purchasing a solar lamp would mean taking away from the limited household incomes that barely meet people’s basic standards of living.

Working with d.light, an international social enterprise that specializes in solar light and power products, the BHER project will use funds raised through this campaign to secure at-cost solar-powered lamps for students in the BHER program.

Help bring light to Dadaab’s refugee and local university students’ lives, studies, and futures by contributing today.

Over the next 4 years, The BHER project will serve approximately 800 refugee students. For a contribution of about $42 CAD, you will provide one student with a solar-powered lamp that will help them through the duration of their studies. This means that for every $1,000 CAD raised, 23 students will be provided with a resource that will give them the freedom to do coursework at home during the evening. For many refugee and local students – particularly women – your contribution can make the difference that enables them to complete their education.

![Somali refugees at the Dadaab refugee complex in attend the celebrations to mark World Refugee Day on June 20, 2012. [Abdullahi Mire/AFP]](http://sabahionline.com/shared/images/2014/03/11/somali-refugees-dadaab-340_227.jpg)