Category Archives: Community Scholar

Roma Rising Exhibit — Toronto

Roma Rising Exhibit — Opening Sept 19 at 12:00pm (Osgoode Library)

A collection of photographs of members of the Canadian Roma (Gypsy) community is now on display at the Osgoode Hall Law School Library. The exhibit, Roma Rising / Opre Roma – Portraits of A Community (romarisingCA), was created to challenge stereotypical views of the Roma community. Sponsored by the Roma Community Centre (RCC) based in Toronto, the exhibit features 24 black-and-white portraits by photographer Chad Evans Wyatt of Canadian Roma who are successful in middle- and professional-class occupations. The exhibit will be on display until October 4, 2013.

While you are welcome to view the exhibit during regular Library hours, you are also invited to attend the official opening of the exhibit which will take place in the Law Library on Thursday, September 19, 2013 at 12:00 pm. Associate Dean James Stribopoulos, Professor Sean Rehaag and Gina Csanyi-Robah (Executive Director of the Roma Refugee Centre) will offer brief remarks about the exhibit.

You can find out more about the event here

Black France

How long have Africans been in France? What are there experiences? What does it mean to live in a country where the National Assembly voted in favor of a bill to remove the words ‘race’ and ‘racial’ from the country’s penal code?

Check out the series by AlJazeera on “Black France” to engage with some of these questions!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_detailpage&v=3YO2i0ZWV_Q

What happens when refugees go back home?

Moulid Hujale tells us about returning in: “My journey back to Somalia,”

Sourced from IRIN: By Moulid Hujale

MOGADISHU, 27 August 2013 (IRIN) – My journey back to Somalia, my home country, was a dream and a choice I always wanted to achieve. I wanted to live on the soil of my ancestors away from the congested refugee camps of Dadaab and far from the tall buildings of Nairobi that hosted me temporarily and offered me an opportunity to be a citizen in a second home where I grew up and studied peacefully.

After almost two decades in Kenya, I finally decided to return to the country of my origin after getting an exciting opportunity to work with the Ministry of Education in order to bring hope to the next generation and give back my skills and knowledge to my community.

I arrived at Aden Ade International Airport in Mogadishu on 26 July, a Friday morning. Almost all the passengers in the plane I was travelling in were Somalis, mostly returning from abroad. The small airport and its facilities were very busy and chaotic. It was far from international standards – with all the signs of the wreckage of war and unfinished reconstruction under way.

I was driven by a colleague in a taxi through many checkpoints with heavily armed guards comprised of AMISOM [African Union Mission in Somalia] and Somali troops. We drove along the airport road, one of the city’s most dangerous, with heavily armed security personnel at frequent road blocks.

There was a high security alert. I was extremely scared and could not believe my eyes. I thought they were clearing up the aftermath of a fight in the city, but little did I know that this was the order of the day in Mogadishu.

That day was unique in particular because it was the 17th day of Ramadan, a day on which every year [militants] are known to carry out deadly attacks to commemorate one of the Islamic holy wars that took place on this day in history.

We turned onto another highway that was also very scary for newcomers like me, but normal for local residents. It is Maka Al-Mukarama road, known for nearly non-stop hooting vehicles – mainly small shuttle buses with overloaded passengers, some hanging onto the doors and windows while the conductor clings to the rear side as he shouts for more passengers.

“Stay calm, this is normal”

This road is also one of the busiest roads in Mogadishu; it directly connects State House and the airport. The traffic is hectic and it is controlled by traffic police, military and administration police. Gunshots, I was told, are used as “traffic lights” to disperse jams and as warning shots.

Surprised at my anxiety and restlessness, the driver said: “My friend, stay calm, this is normal.” I smiled to respond positively but did not say a word. I was speechless until we reached Taleh residential area.

This area was relatively calm. Residents were busy with their daily activities during the Ramadan fast.

I stayed indoors on advice from family and friends in Kenya. I was told to minimize my movement in the city and avoid crowded areas. However, I felt very insecure even inside my room because I was traumatized by the deafening sound of gunshots outside. I hear gunshots all day, like I hear the call to prayer, and it makes me sick.

I could not understand why there are all these gunshots in the streets. Then I recall the guys I saw along the airport road and the other young men in government uniforms hanging onto the sides of vehicles speeding up Maka Al Mukarama road all with firearms pointing at the pedestrians and other passing vehicles, their fingers on the trigger.

The following day was another unpleasant experience. The Turkish embassy was attacked. I could hear the blast not far from where I was staying. The thought of going back to Kenya came to my mind but it eventually faded away later that night when the commotion ended and I saw the story on TV.

Meanwhile, the locals are fully engaged in their day-to-day activities, indifferent to what is happening around them. Besides the gunshots, explosions and chaos, there are parallel constructions, business transactions and celebrations on the eve of the Eid festival after Ramadan.

Toy guns

One of the most striking things I saw at this time were all types of big toy guns displayed in the shops for children to play with during the Eid celebrations [marking the end of Ramadan]. On the actual Eid day, I saw children smartly dressed happily enjoying the day but with huge toy guns hanging on their shoulders, shooting one another typically as though they were on a battlefield. When you see the toy guns you will never understand… I was really disappointed how these innocent children are being brought up with such destructive weapons.

Is it because their parents are ignorant? What message does it portray? How will the fresh minds of these children be affected? What does it symbolize? I think we lost two generations already and the third one is growing in a world of lawlessness and ignorance. We have to do something about this and educate today’s parents and youth to save Somalia’s next generations.

Reporting for work

I reported to work the following week. I met new friends. The environment, the people and the job were all fresh and awesome. I felt very fortunate when I sat at a desk where the flag of Somalia flies right beside the computer, a reminder of my identity.

I was motivated to be part of a young, passionate team mostly from the diaspora who came to work with the Ministry of Education. We are specifically designated to work on a unique programme that was independently run by the Ministry, unlike other partner-led projects.

This was a project dubbed “Aada Dugsiyada” (Go to School Initiative) aimed at getting one million children into free and quality public schools by 2016. All the schools in the country are privately run so the challenge of starting the first free public schools after more than two decades of war lay ahead of us.

However, the feedback from all the people – including stakeholders, donors, local media and authorities – is overwhelmingly positive.

Running a whole government ministry that has not been functioning for over 20 years is a nightmare, and requires huge support both financially and in terms of dedicated professional human resources.

Standing firm

I did not understand what “failed state” really meant until I reached Mogadishu. To be honest, I only thought the term was used just to describe how much our country was damaged, but the true picture dawned on me when I explored the capital, where all government institutions are managed.

All the concerted efforts that were made to rebuild this country were focused on primarily handling the security, which still remains a stumbling block, thus leaving the gap for all other vital areas that a fully functioning nation with its dynamic society needs.

But, interestingly, how do you describe those people who have been courageously living in the midst of all these clashes, the devastation, droughts, famine and atrocious terror situations for decades and counting – yet have been standing firm to keep going with privately run business institutions, booming markets, private schools, social and economic development, while those in diaspora have been supporting them financially doing odd jobs in odd hours and facing the challenge of detention, discrimination and death for the same course.

I was really moved when I saw how the old Somali currency is being utilized in Mogadishu. In any business transaction, no one rejects the torn, ragged and spoilt ones because they fully know that there is no replacement or functioning central bank that regulates the money, so they are happy to keep going with what they have and make their lives easy.

I am, therefore, pleased to say that the Somali community to which I belong is exceptionally resilient, productive, hardworking, courageous, intelligent and determined. These are people who can reach beyond measurable heights in the 21st century if only our own political leaders and their foreign stakeholders act honestly in all their endeavours to stabilize Somalia for a better tomorrow.

Backpacks From the (Mexican) Border

PHOTOGRAPHS BY Richard Barnes

In January 2009, an anthropologist named Jason De León began spending a lot of time near the United States border south of Tucson. On the Mexican side, he interviews would-be migrants about to try an illegal crossing. On the American side, he collects what is discarded by those who make it — among other things, clothing soiled by the passage and the backpacks in which they carried clean clothes. Many of these items have been exhibited at the University of Michigan, where De León is the director of the Undocumented Migration Project; one of his collaborators, the photographer Richard Barnes, helped select the backpacks for the following pages. Says De León: “I realized that you have this highly politicized social process that’s incredibly clandestine and misunderstood. I just want the public to have a better understanding of what it actually looks like.”

- UNDOCUMENTED IMMIGRANTS IN THE UNITED STATES: 11 million

- WOULD-BE IMMIGRANTS APPREHENDED DAILY AT THE BORDER SOUTH OF TUCSON: 330

- ARTIFACTS COLLECTED FOR THE UNDOCUMENTED MIGRATION PROJECT: more than 10,000

See more here

What does it mean to be “Other” in Canada?

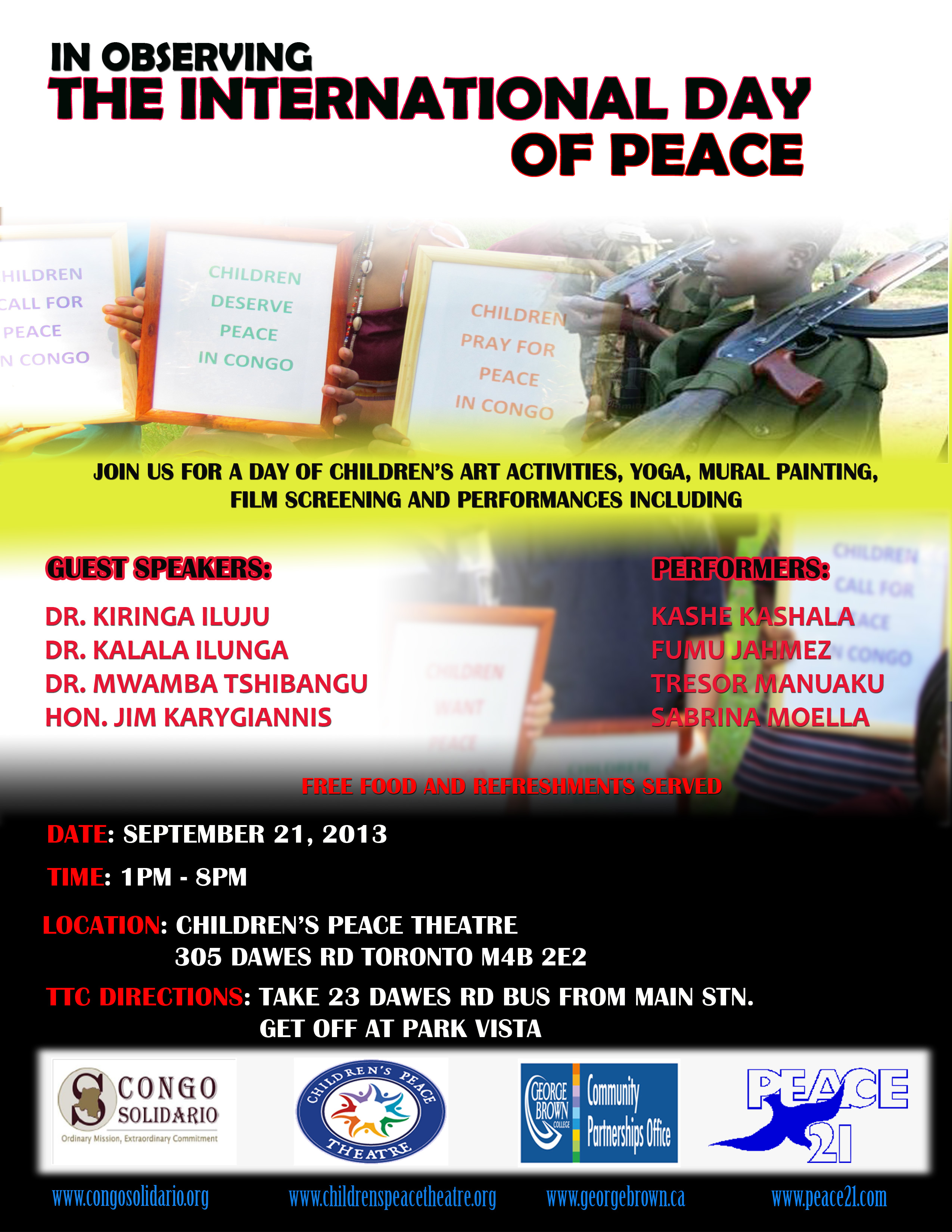

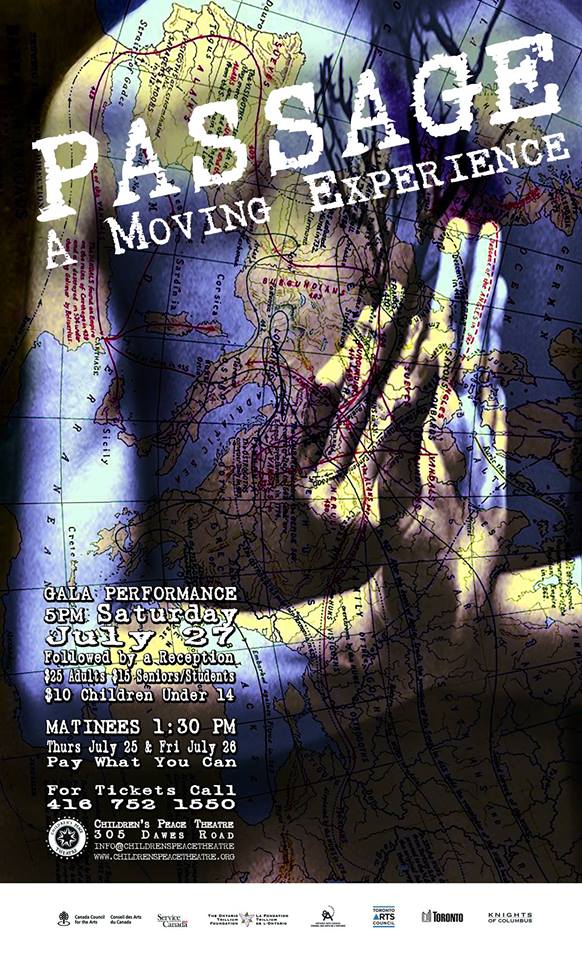

What does it mean to be “other”? in this society? Check out a scene “in progress” from the 2013 CPT Peace Camp. The polished/finished version of this scene was included in the final production of “Passage: A Moving Experience”, and we will post clips of the play as soon as is possible. In the mean time, click on the picture link below and enjoy and mull over this clip that follows!

The Art of “Passage(s)”

Aside from brainstorming ideas through theatre and music, visual art was also a key part of the making of “Passages: A Moving Experience.” Click on the picture link below and walk with Melis, the co-visual art director at this year’s Peace Camp, as she describes some of the art that was part of this production.

Don’t forget to go see “Passage” this Friday and Saturday!

Last day(s) of Peace Camp & Rehearsals for P(erformance) Day!

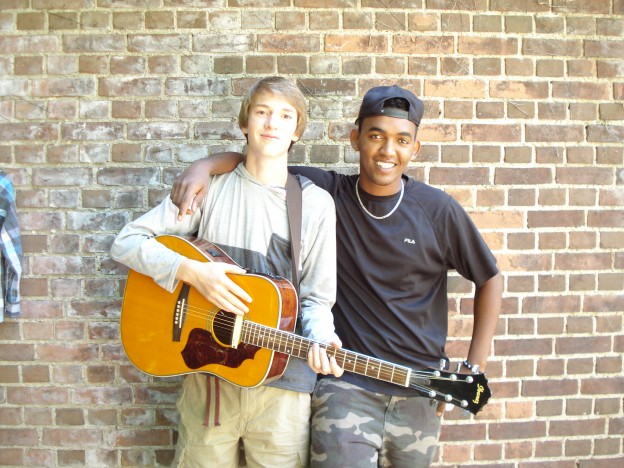

Friendship, sharing, prop-making, compassion, posing, hard work and much more went into the rehearsals for the final performance(s) of “Passage: A Moving Experience“. Check out the photos from these process(es) below!

- Meditation with Kwanza

- More music making with Brownman

- Friends help friends learn the music in “Passage”

- Practicing super star pose!

- Perfecting our lines

- Perfecting super star pose!

- Also perfecting superstar pose

- Scene making/brainstorming/digesting

- Creating with our bodies

- Burdened by migration

- Getting carried away by the magic!

- Trying different roles for play!

- Scene from play

- Friends help friends deal with persistent camera person!

- Friends smile together for persistent camera person!

- Perfecting individual super start pose!

- Friends perfecting (group) superstar pose

- Feedback time

- Lyrics and lessons from “Passage”

- Set creation

- Doritos as props!

- Scenes from rehearsal

- Why did you think you were welcome? Migration and other stories

- Sharing amidst rehersals

- Ayesha breaks it down!

- Polishing scenes for performance(s)

- Making props for performance

- Finished props for performance

Check out the Toronto Star’s write up on Peace Camp!

Toronto summer camp theatre explores the journey of young migrants

The struggles and hopes of being a young immigrant unfold at Toronto Children’s Peace Theatre.

NICHOLAS KEUNG

Sirak Tesfu, 19, from Eritrea, and Rosa Solorzano, 18, from El Salvador, both participate in the Children’s Peace Theatre’s gala production, Passage: A Moving Experience. Article accessed from here

A teenage boy from Eritrea recalls the awkwardness of reuniting with his father, whom he had not seen for 13 years.

A young woman from Antigua remembers the cold reception she got when she returned to Canada, the birthplace she was scooped away from as a toddler.

A refugee girl from El Salvador is afraid of bonding with others because of the experience of losing friends when she moves again.

All three are members of the Toronto Children’s Peace Theatre summer camp this year, and their stories, along with others, will be part of the group’s performance, Passage: A Moving Experience, which debuts Thursday at the Dawes Rd. theatre.

Through art installations, such as a bed-spring sculpture about “home,” to song compositions with lyrics about migration and storytelling, the youth and their professional artist mentors will explore the young migrants’ journeys, struggles, challenges, hopes and dreams.

“It feels good to get these stories out there so people know what we have gone through to be here,” said Sirak Tesfu, 19, who, along with his mother and little sister, was separated from his father, a refugee, as a kid before joining him here two years ago. They came from Eritrea via Sudan.

“I only knew my father by phone. It was strange to see him.”

Now in its 13th year, the theatre’s summer camp chose to produce a show about youth migrants after one of its artists had his refugee claim rejected and was deported to Mexico last fall.

“Born in Canada, I grew up at a time when we were making strides in humanitarian causes, but our immigration and refugee system has drastically changed in recent years. Canadians can’t be proud of what’s happening,” said the theatre’s artistic director, Karen Emerson.

“These stories need to be told. These voices need to be heard.”

In the past, the theatre and its campers have tackled various social justice themes, with shows about food security (“Eat It Up”) and child soldier/labour (“Up In Arms”).

Unlike Tesfu, who spoke Tigrinya and must learn English from scratch, Amber Williams-King faces no language barrier. Born in Toronto, she was taken to Antigua at age 2 but returned alone four years ago.

“I was a citizen, but people saw me as a foreigner. English is my first language, but I had to change my accent so people could understand me,” said the 23-year-old.

“We need to create a sense of understanding of the different people who make up Canada, accepting and appreciating the differences. Canadians have the responsibility to live up to its name as a multicultural mosaic.”

Rosa Solorzano and her family fled El Salvador for the U.S. before arriving in Toronto two years ago. She said she always isolated herself from others because she hated the experience of leaving her friends behind. But the summer camp has brought out her inner self.

“It sucks when you can’t bond with people. You just don’t know when you have to move again,” said Solorzano, 18, who graduated from high school but cannot go on to higher education because her family is still waiting for a refugee hearing.

“I’m surprised how much I’m enjoying this. I am learning something new and the kids just have so much energy and so many great ideas.

What are your thoughts on this article? Feel free to share them below!